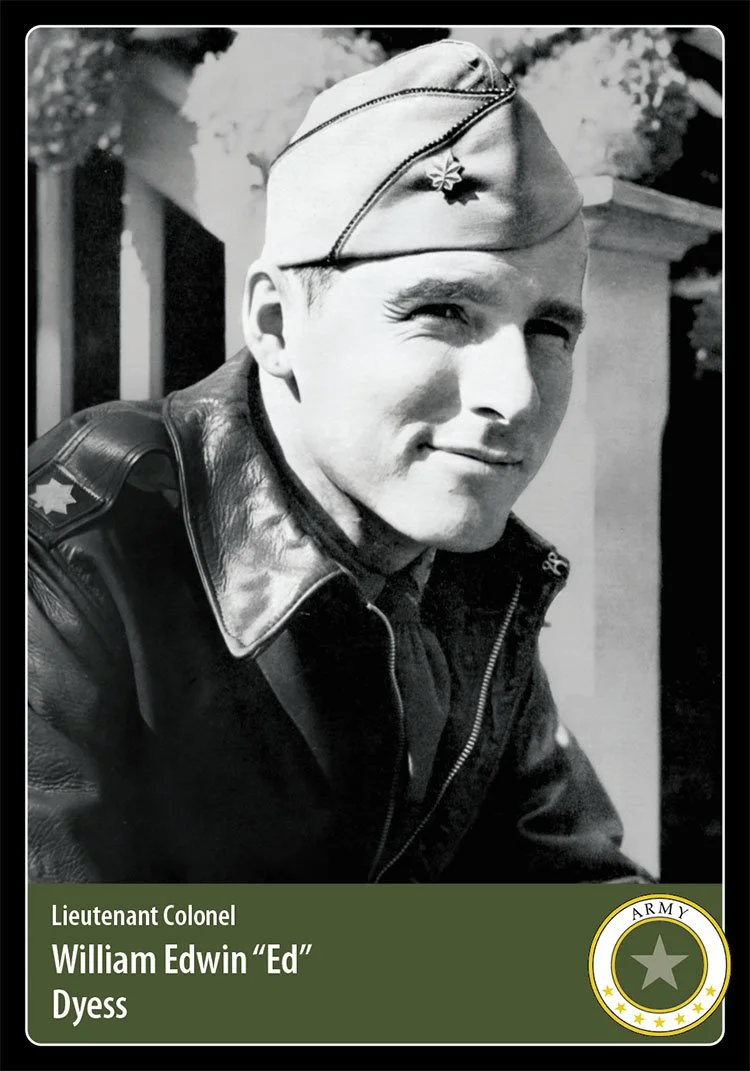

Hero Card 100, Card Pack 9

Photo: United States Air Force (digitally enhanced)

Hometown: Albany, TX

Branch: U.S. Army (Air Forces)

Unit: 21st Pursuit Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group, Far East Air Force Division

Military Honors: Distinguished Service Cross (2), Silver Star (2), Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross (2), Soldier’s Medal, Prisoner of War Medal, Purple Heart

Date of Sacrifice: December 22, 1943 - Burbank, California

Age: 27

Conflict: World War II, 1939-1945

William Edwin “Ed” Dyess was born on August 9, 1916, in the small town of Albany, Texas. His father, who was a judge and an educator, took young Ed on his first airplane ride when a barnstormer passed through town. As a teenager, Dyess secretly arranged to get flying lessons from another barnstorming pilot.

After graduating from Albany High School, Dyess went to John Tarleton College in nearby Stephenville, preparing to study law at the University of Texas in Austin. While at Tarleton, he was president of his class and commander of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) detachment.

During the summer between schools, Dyess worked in the Texas oil fields as a roustabout. His interest in aviation grew, and he sought his father’s help to instead receive an appointment to the Army’s premier base for pilot training, located just 250 miles south of Albany, near San Antonio. Ed Dyess graduated from Advanced Flying School at Kelly Field on October 6, 1937. He joined the Army Air Corps, which later became the Army Air Forces, with a commission as a Second Lieutenant.

Assigned to the 21st Pursuit Squadron, Dyess was soon promoted to First Lieutenant and commander of the squadron. Dyess and the squadron were deployed to Nichols Field in Manila, Philippines, in October 1941. Within hours of the December 7, 1941 surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the Japanese also attacked the Philippines.

The Department of Veterans Affairs recounts Dyess’s actions in the weeks that followed:

Dyess led his squadron on a raid, which destroyed a convoy of Japanese trucks and shot down several enemy fighters. Dyess was promoted to captain in January 1942. In the next few months, Dyess led other successful missions, including the first amphibious landing in World War II, which killed about 75 elite Japanese troops, and an air raid that resulted in the massive destruction of a Japanese supply depot at Subic Bay.

The Japanese forces soon overwhelmed the combined Filipino and American forces, who were forced to surrender on April 9, 1942. At the Bataan airfield west of Manila, the defeated forces scrambled to evacuate. Dyess, along with thousands of Filipino and American forces were captured. According to the National Museum of the United States Air Force:

As Bataan was about to fall, Capt. Dyess chose to stay with his men rather than evacuate, giving his seat on the last plane out to the future president of the UN General Assembly, Philippine Army Col. Carlos Romulo. After surviving the horrors of the [Bataan] Death March and imprisonment, he escaped from his captors with several other prisoners in 1943. He met with Filipino guerrillas, participated in their activities for three and a half months, and left the Philippines in a U.S. submarine. Capt. Dyess and his fellow escapees reported the Bataan Death March atrocities to General MacArthur. The American public first heard of the horrors of the Death March in early 1944 after the War Department allowed the press to tell Capt. Dyess’ story.

The Chicago Tribune and other newspapers were given permission by the War Department to publish a series of articles called “The Dyess Story” about Japanese atrocities during the Bataan Death March. Dyess’s accounts had an immediate impact on world opinion and greatly aided the war effort. His descriptions were later compiled into a book: Bataan Death March: A Survivor’s Account. An excerpt:

I am going to describe in detail the daily life, the misery and the torture that characterized the 361 days I existed in three prison camps and a prison ship; a period of starvation and horror that took the lives of about 6,000 American and many thousands more Filipino war prisoners out of a total of 50,000 men who started from Bataan. Finally, I will tell you how a few of us escaped.

After two months of recovery, Dyess was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was eager to return to combat. He began training to deploy to World War II’s European Theater. For his actions in the Philippines, Dyess received numerous awards including two Distinguished Service Crosses:

First Distinguished Service Cross citation

For extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Pilot of a P-40 Fighter Airplane in the 21st Pursuit Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group, FAR EAST Air Force, while participating in a bombing mission against enemy Japanese surface vessels on 2 March 1942, over Subic Bay, Philippine Islands. On this date Captain Dyess hung a 500-pound bomb with a jury-rigged bomb release on a P-40 and, with three other pilots, bombed and strafed Japanese shipping in Subic Bay. Three times that day he braved heavy flak, destroying or damaging several small vessels, warehouses, and supply dumps. The personal courage and devotion to duty displayed by Captain Dyess on this occasion have upheld the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, the Far East Air Force, and the United States Army Air Forces.

Second Distinguished Service Cross citation

For extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving with Philippine Guerilla Forces during the period 4 April 1943 through 20 July 1934. Major Dyess was one of ten men including two Naval Officers, three Air Corps Officers, and two Marine Corps Officers who escaped after nearly a year in captivity after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor. The ten men evaded their captors for days until connecting with Filipino Guerillas under Wendell Fertig. The officers remained with the guerillas for weeks, obtaining vital information which they carried with them when they were subsequently evacuated by American submarines. Their escape was the only mass escape from a Japanese prison camp during the war. The personal courage and devotion to duty displayed by Major Dyess during this period have upheld the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, the Prisoner of War, and the United States Army Air Forces.

On Dec. 22, 1943, Lt. Col. Dyess was on a routine training flight near Los Angeles, California when his P-38 caught fire while he was over a populated area. He could have made a safe landing on a Burbank highway, but when a motorist appeared, that was not an option. Rather than bailing out and risking harm to civilians, Dyess stayed with his burning aircraft, crashing it in a small vacant lot. Lieutenant Colonel William “Ed” Dyess was 27 years old.

For his courage in battle, as a prisoner of war, and for selfless sacrifice, Dyess Air Force Base was named in his honor. The base is located in Abilene, Texas, just 35 miles southwest of his hometown of Albany.

Sources

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, VA News: America250: Army Air Forces Veteran William Edwin “Ed” Dyess

National Museum of the United States Air Force: One Man Scourge: William E. Dyess

Lt. Col. William E. Dyess: Bataan Death March: A Survivor’s Account

History Channel: Bataan Death March

San Angelo Evening Standard, 08 May 1945: Col. Dyess, A ‘One-Man Scourge of Japs’, Escaped Prison Camp

Texas State Historical Association: Dyess, William Edwin (1916-1943)

Military Times, Hall of Valor Project: William Edwin Dyess

Warfare History Network: Hero to the End: Airman William “Ed” Dyess on the Philippines

Traces of War: Dyess, William Edwin “Ed”

The Historical Marker Database: Lt. Colonel William Edwin Dyess

Burial Site: Find a Grave