Hero Card 187, Card Pack 16

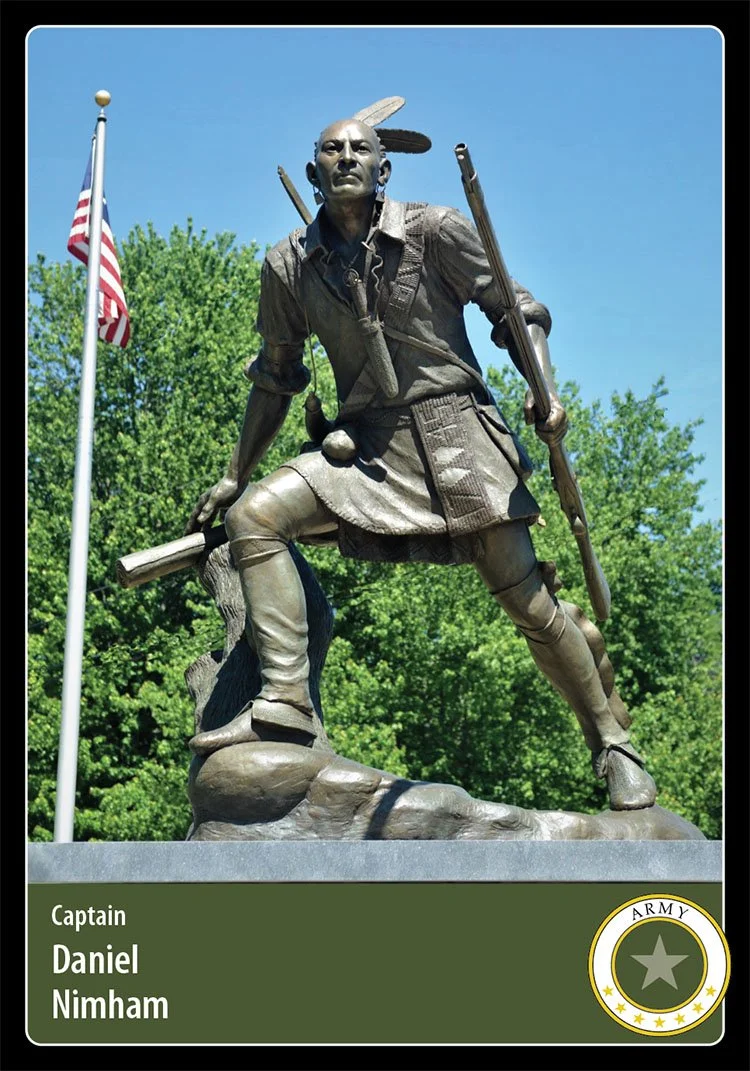

Artist’s representation by Sculptor Michael Keropian. Photo: Wikimedia, Public Domain (digitally enhanced)

Hometown: Fishkill, NY

Branch: Continental Army

Unit: Stockbridge Indian Company

Date of Sacrifice: August 31, 1778 - KIA in Cortlandt’s Ridge, New York

Age: 52 (approximate)

Conflict: Revolutionary War, 1775-1783

Daniel Nimham was a diplomat, a warrior, and the last sachem (leader) of the Wappinger tribe in New York’s Hudson Valley. Fighting for the British in the French and Indian War and against them in the Revolutionary War, Nimham was commissioned as a Captain in the Continental Army. He was with Gen. George Washington at Valley Forge and later gave his life for the American cause—refusing to surrender in the Battle of Kingsbridge.

The Wappingers

Prior to the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the Wappinger people lived along the eastern banks of the Hudson River, from New York’s Manhattan Island to Connecticut. In most Algonquian languages, “Wappinger” can be translated as “easterner.” Their name for what was later called the Hudson River was “Muhheakantuck”—or “the river that flows both ways”—because of the incoming flow of the ocean tide against the river’s natural current.

The Wappinger people lived in seasonal camps, regularly moving to follow the changing availability of fish, game, and plant life. Later developing the practice of agriculture—such as beans, corn, squash, sunflower, tobacco—they’d establish temporary settlements along the Hudson, sometimes surrounded by a wooden palisade (defensive walls made of tree trunks).

Through the 1600s-1700s, the region hosted a variety of native tribes, including Munsee (also called “Lenape”), Mohican, Mohawk, smaller bands, Africans, and Dutch traders. According to the National Parks Service, “The relationships between these groups ranged from cooperative trade, to exploitive slavery, and outright warfare.”

Adapting Cultures

As war, epidemic diseases, and intermingling with other area tribes reduced the Wappingers’ numbers to the hundreds, Daniel Nimham was born sometime around 1726. Different cultures colliding, trading, and adapting to each other was commonplace in the region. By the mid-1700s, Nimham had encountered European settlers of the valley as a young man, learned English, and kept friendly relations with them.

As an adult he became the sachem of his people. An experienced warrior and diplomat, Nimham and some 300 Wappinger men fought on the side of the British during the French and Indian War, which lasted from 1754 to 1763.

At that time, New York and Connecticut were colonies under the British Crown. Nimham and the Wappinger people became embroiled in a dispute when the family of Adolphus Philipse, a wealthy New York City merchant, made an expanded land claim into Wappinger territory.

Daniel Nimham had developed a reputation for diplomacy and traveled to England to petition his case. Returning home, his dispute came before the New York Common Council in 1765. According to the American Battlefield Trust, “with a questionable deed presented by the defendant [Philipse] and hesitance to set an adverse precedent, the Council ruled against Nimham and the Wappinger.”

Joining the Revolution

Having fought for the British Crown, the decision left a bitter taste in the mouths of the Wappingers. When the colonies revolted against England and declared independence on July 4, 1776, Daniel Nimham and his people joined the cause. He saw the value of the Patriot cause and likely understood the possibility of negotiating the return of Wappinger land if he was to fight alongside the colonists.

Nimham was given a commission as a captain in the Continental Army. He was essential in developing an important force for the American cause, having recruited warriors from native communities stretching from Canada to the Ohio Valley.

Daniel’s son, Abraham Nimham, was given command of the 60-man “Stockbridge Indian Company,” based out of Stockbridge, Massachusetts. A Hessian officer, Johan Van Ewald, recalls,

Their costume was a shirt of coarse linen down to the knees, long trousers also of linen down to the feet, on which they wore shoes of deerskin, and the head was covered with a hat made of bast [plant fiber]. Their weapons were a rifle or musket, a quiver with some twenty arrows, and a short battle-axe, which they know how to throw very skillfully. Through the nose and in the ears they wore rings, and on their heads only the hair of the crown remained standing in a circle the size of a dollar-piece, the remainder being shaved off bare. They pull out with pincers all the hairs of the beard, as well as those on all other parts of the body.

Warriors for the Cause

When the fighting began, Daniel Nimham joined his son’s Stockbridge company militia scouts. Daniel and Abraham served alongside Gen. George Washington at Valley Forge, fought in the Battle of Saratoga (New York) and in the fighting at Cambridge, Massachusetts. They also supported troops led by Gen. Marquis de Lafayette.

Serving under Virginian General Charles Scott in 1778, the Stockbridge militia company was assigned to patrol the northern border of New York City—then controlled by the British—and gather intelligence on enemy movements.

On August 20, 1778, the Stockbridge company ambushed a British force north of New York City, killing one light cavalryman and wounding another. News of the attack spread. The British put together a force of 500 British regular troops, Hessians (German troops hired by the British) and Loyalist (colonists loyal to the Crown) troops.

The Stockbridge Massacre

On August 31, 1778, the British set a trap for the Stockbridge militia on Courtland’s Ridge, in what is today The Bronx borough of New York City. Nimham’s 60 warriors were drawn into the open upon sighting a group of Hessian forces, and British Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe’s light infantry struck and hit the Stockbridge company’s left flank.

Surrounded and outnumbered more than 8 to 1, the Stockbridge company fought back in hand-to-hand combat. Simcoe later described the bloody scene that became known as the Battle of Kingsbridge, or the Stockbridge Massacre: “The Indians fought most gallantly; they pulled more than one of the Cavalry from their horses.” Simcoe recounted that Daniel Nimham called out to his warriors that “he was old and would stand and die there.” He was cut down and killed by Private Edward Wight, a British light cavalryman. Abraham Nimham would also be lost in the battle.

Remembering a Patriot

In New York City’s Van Cortlandt Park, a Chief Nimham Memorial monument has been placed on the field where the Wappinger (now called “Stockbridge”) warriors gave their lives for the American cause. In Putnam County, New York, overlooking the Hudson River, Mount Nimham was named in his honor.

In the town of Fishkill, New York, sculptor Michael Keropian was commissioned to create a bronze statue of the great Wappinger sachem Daniel Nimham. The statue, standing on the Wappinger’s ancestral land, was dedicated in a ceremony on June 11, 2022.

Fate of the Stockbridge

After American independence was won, Gen. Washington wrote that the Stockbridge “remained firmly attached to us and have fought and bled by our side; that we consider them as friends and brothers.”

With so many Stockbridge men lost, growth for the tribe was difficult. Despite their service in the Continental Army and their friendship and alliance, land pressures continued after the Revolutionary War. Survivors and families of the fallen Stockbridge company combined with other native tribes and moved to Oneida County in mid-state New York.

When construction of the Erie Canal began after the War of 1812, land pressures again forced the Stockbridge to migrate, this time to Bowler, Wisconsin, 60 miles northwest of Green Bay. The Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians is now federally recognized as an American Indian nation.

Listen to the Grateful Nation Project recording of CPT Nimham’s story on Our American Stories podcast >

Sources

American Battlefield Trust: Daniel Nimham

American Indian Magazine: The Road to Kingsbridge: Daniel Nimham and the Stockbridge Indian Company in the American Revolution

National Park Service, Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area, New York: Dutch & Native American Heritage in the Hudson River Valley

Daughters of the American Revolution: Remembering the Sacrifice of a True Patriot

Michael Keropian Sculpture: Sachem Daniel Nimham

The Creation of the Daniel Nimham Sculpture (Video)

Burial Site: Find a Grave