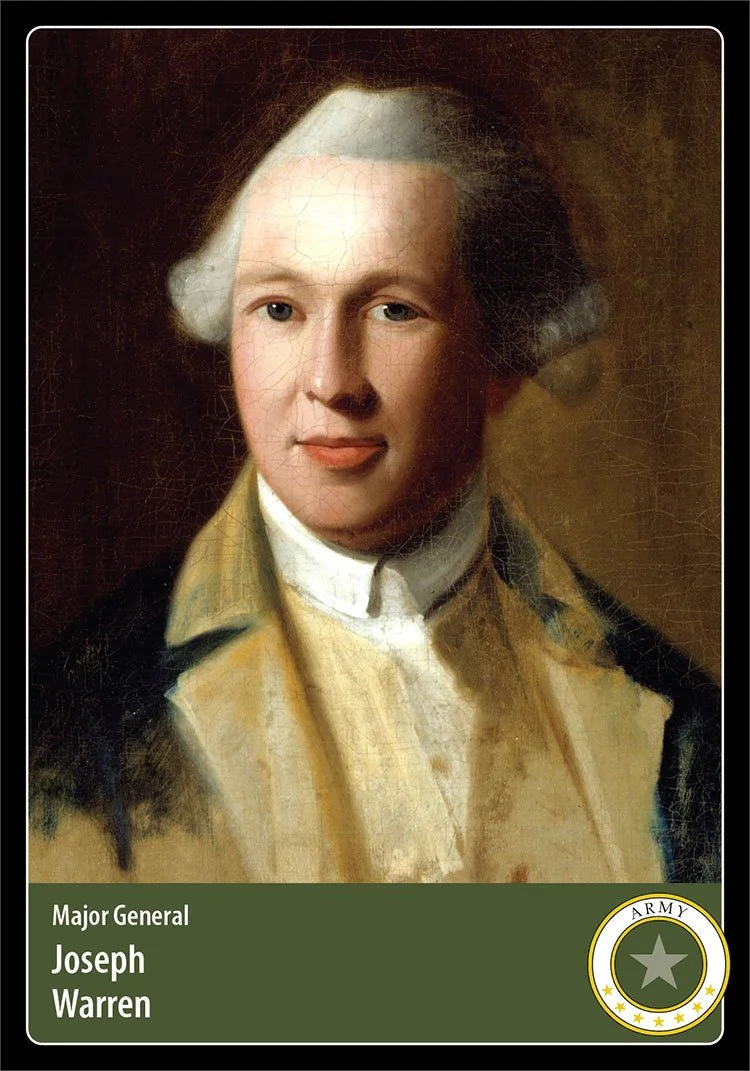

Hero Card 70, Card Pack 6

Oil painting by John Singleton Copley C. 1772 (Public Domain)

Hometown: Boston, MA

Branch: Continental Army

Unit: Massachusetts Patriot Militia

Date of Sacrifice: June 17, 1775 - KIA at Breed’s Hill, Charlestown, Massachusetts

Age: 34

Conflict: Revolutionary War, 1775-1783

Many Americans are unfamiliar with Joseph Warren, a Boston doctor and patriot leader who risked everything to defy the “intolerable acts” of the British Crown. Dr. Warren is one of the most important figures in early American history.

For a decade leading up to the Revolutionary War, Warren was an architect of the colonial rebellion. A leader of the Massachusetts Patriot Militia, his actions and incendiary writings helped spark the insurrection in Boston that grew to become the American Revolution.

Early life

Joseph Warren was born on June 11, 1741, on a farm in Roxbury, Massachusetts to Joseph and Mary (Stevens) Warren. From the hills of their country town just two miles south of Boston, the Warren family could see the bustling harbor town that was growing to become the most important city in the British North American colonies.

On the farm, the family grew Warren Russet apples (also called “Roxbury Russet”)—today thought to be one of the oldest known apple varieties in North America. Through long hours of manual labor, young Joseph learned the value of hard work and the benefits of buying, selling, and trading a variety of farm-produced goods in a rapidly growing market.

Education and medical practice

The elder Joseph Warren was a very pious man, even by Puritan standards. Evenings would be spent in the reading and diligent study of the Scriptures. With his parents’ strong Calvinistic beliefs and placing a high value on education, the younger Joseph Warren was sent to nearby Roxbury Latin School, and later to Harvard College in Cambridge.

At the time, Harvard was already a century old, and one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in British North America. It was also one of the few available to students of modest means. Admission to Harvard was based on a series of tests, mostly oral.

Upon graduation from Harvard, Warren accepted a “one-quarter of a year” position as a master at his former Roxbury Latin School. Later he returned to Harvard to pursue a Master of Arts degree in medicine, followed by an apprenticeship with an established physician—Dr. James Lloyd. From Lloyd, Warren learned how to run a successful medical practice, and he opened his own practice in Boston in the spring of 1763.

Within months, severe outbreaks of smallpox would both challenge the young Dr. Warren and at the same time demonstrate his courage and selflessness to the community in Boston. The practice of inoculation was controversial at the time, and many of Boston’s elite fled the city to wait out the epidemic in their country homes. Warren remained, treating hundreds of infected patients at Castle Williams, a nearby island fort set up to isolate the sick.

Among the patients whom Dr. Warren later considered friends were John and Abigail Adams and their son, John Quincy Adams. Some 5,000 people were inoculated, and less than one percent died from smallpox. A grateful public took notice of Dr. Warren as one of the heroic “gentlemen doctors” who saved their lives. His practice grew, as did the public’s trust and esteem for the young Joseph Warren.

Growing resentment Toward the Crown

As the epidemic passed and Boston returned to normal routines, across the ocean the British Parliament was looking at the American colonies as a source to raise revenues. Passing a series of new taxes, including the Sugar Act in 1764, the Parliament levied heavy taxes on the colonies.

As the colonies angrily protested the taxation without proper representation, it seemed the British Army was present more to enforce unjust laws than to protect the colonists. Along with his fellow Bostonians, Joseph Warren’s resentment toward British authority grew stronger with each “intolerable act” passed in London.

When the Stamp Act, a direct tax on items purchased in the colonies, was passed by Parliament in March of 1765, opposition to British rule united Boston’s lower, middle, and upper classes in protest. Acts of defiance, vandalism and rioting surged.

Dr. Warren began to openly defy local British authorities through speeches at numerous town meetings, and series of articles in the Boston Gazette under the pseudonym “A True Patriot.” Warren argued for the right to self-government and colonial home rule, and was one of the original members of the underground “Sons of Liberty”—a grassroots group of agitators.

Through his growing political activism and involvement with the Free Masons, Warren developed close friendships with fellow patriots Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere.

By 1773, the tension between American Colonials and the British Parliament came to a head with the passage of the Tea Act. In response, the Boston chapter of the Sons of Liberty staged what we now know as the Boston Tea Party, defying the British Crown.

Architect of the Rebellion

In May of 1774, the British Parliament was losing patience. Commander of British forces in North America, General Thomas Gage, took over as Governor of Massachusetts, and taxes charged to the colony increased tenfold. Gage outlawed the Massachusetts Congress, and charges were filed against the agitators John Hancock, Samuel and John Adams, and Joseph Warren.

By mid-June, the rest of the American colonies had adopted Boston’s cause as their own. In the Evening Post, Warren wrote, “Act, then, like men. Appoint a general congress from the several colonies. Unite as a firm band of brothers, and ward off the evil intended.”

As more British ships and troops arrived in Boston, Warren chaired a “Committee of Safety” to gather and store arms and gunpowder in case the citizens were attacked by British forces. The original intent was to serve as a means of defense. In Philadelphia, the First Continental Congress was assembled to gather representatives from all the colonies.

The Suffolk Resolves

In a reaction to the British dissolving Massachusetts’ provincial representative government, Joseph Warren organized meetings of representatives from every town in Boston’s Suffolk County. Meeting in the Dedham home of Richard Woodward, and later the Milton home of Daniel Vose, Warren was chosen to draft a proposal and statement of protest.

The resulting “Suffolk Resolves” declared their refusal to obey any of the “intolerable acts” or the British officials responsible for them. They urged fellow citizens to cease payment of taxes to the Crown, and to begin weekly militia drills. Those appointed to the Governor’s Council by British authorities must resign. British imports would be boycotted, and no exports to England would be allowed.

The document also stated that if General Gage—the new Royal Military Governor of Massachusetts—was to arrest anyone for political reasons, the citizens’ militia would retaliate by seizing Crown-appointed officials as hostages. The Suffolk Resolves were adopted unanimously.

Warren sent Boston silversmith Paul Revere to deliver the Suffolk Resolves to the colonies’ First Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia. The Resolves were the first declaration promoting the complete rejection of British governmental authority over the colonies. The assembled representatives in Philadelphia endorsed the document, which would later serve as a blueprint for the Declaration of Independence.

The Revolution Begins

Paul Revere was to be dispatched a second time by Dr. Warren. Taking note of the British army leaving Boston in long boats across the Charles River, Warren acted quickly. On April 18, 1775, he sent Revere and William Dawes to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock—who had bounties on their heads—and to alert the citizens’ militia that the British army was marching to the towns of Lexington and Concord to confiscate the patriots’ build-up of arms, powder, and ammunition.

With the first shots fired at Lexington, the war for American independence had begun. Joseph Warren hurried to Lexington to join the fight, and narrowly escaped death as a musket ball grazed his head. In the two months between Lexington and the Battle of Bunker Hill, Warren gained a reputation for running to wherever the fighting was most intense. Understanding Warren’s value to the cause of liberty, other patriot leaders believed he was taking unnecessary risks by hurrying to any skirmish that broke out.

Dr. Joseph Warren helped organize a provincial army made up of militia from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. Besides fighting in every battle he could find, Joseph Warren facilitated communication with other colonies, with sympathizers in London and Canada, and he opened negotiations for alliances with six Indian nations.

On June 14, 1775, the Third Provincial Congress made Joseph Warren a major general. That same day, the Second Constitutional Congress in Philadelphia established the Continental Army, unifying the many militia units throughout the colonies for the common defense.

The Battle of Bunker Hill

Two months after the first shots were fired at Lexington, American troops took possession of a field on Bunker Hill, overlooking Charlestown—just across the Charles River from Boston. As usual, Joseph Warren hurried to join the fight.

When Warren arrived, General Israel Putnam and Colonel William Prescott requested that he serve as their commander to repel the British forces. Instead, Warren insisted on resigning his commission as an officer and joining the soldiers where the fighting would be most intense. Over Putnam and Prescott’s objections, Warren was directed to the smaller Breed’s Hill below.

His presence and passion to defeat British tyranny deeply inspired the troops at the forefront of the battle, and would later inspire military leaders throughout the colonies, including George Washington. On June 17, 1775, Joseph Warren was killed instantly when he was struck in the head by a musket or pistol ball in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Although the British Army successfully took the field atop Bunker’s Hill, the cost was high. Of the 2,400 British soldiers engaged, nearly half (est. 1,000) were killed or wounded. The significant casualties inflicted on the world’s greatest military power were a major confidence boost for the inexperienced colonial army, and a first step toward ending the siege of Boston.

Biographer Christian Di Spigna, in his book Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution’s Lost Hero, summed up the importance of Warren’s contribution to the cause of liberty:

[Warren was]…a complex man who helped lead and propel the colonies to declare independence in 1776. Without Warren, the rebellion in Boston would have faltered and possibly ended in failure. Unequivocally one of the most important figures in the movement for independence, Dr. Joseph Warren worked to achieve his vision with his unique arsenal of voice, pen, and sword. He was a founding grandfather of the United States.

Sources

Card Artwork: National Park Service Digital Asset Management System—Oil painting by John Singleton Copley, C. 1772 (Public Domain)

Christian Di Spigna—Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution’s Lost Hero

Revolutionary War Journal—Doctor Joseph Warren: Patriot Leader Killed at Bunker Hill

Dr. Joseph Warren on the Web: Power But Not Justice, Vengeance but Not the Wisdom of Great Britain…Suffolk Resolves

National Parks Service: Dr. Joseph Warren

National Parks Service: Boston—Bunker Hill

Dr. Joseph Warren Foundation

American Battlefield Trust: Joseph Warren

Burial Site: Find a Grave