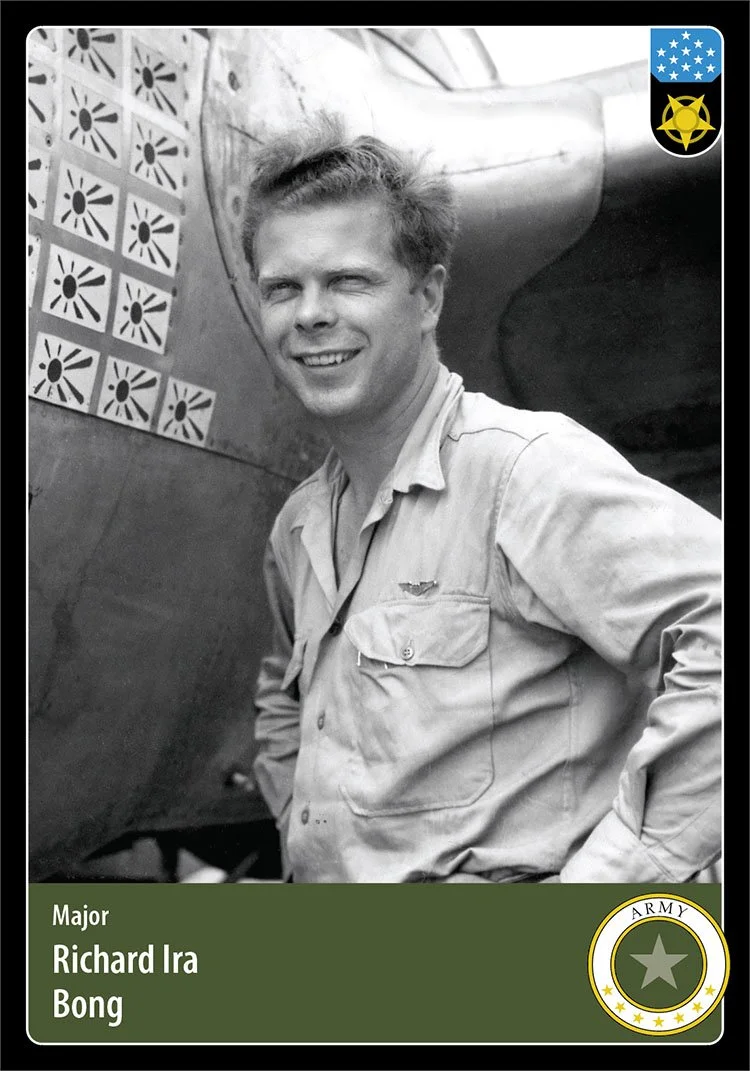

Hero Card 79, Card Pack 7

Photo: Public Domain, retrieved from Our American Stories

Hometown: Poplar, WI

Branch: U.S. Army (Air Forces)

Unit: 49th Fighter Group, 5th Fighter Command, Fifth Air Force

Military Honors: Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star (2), Distinguished Flying Cross (7), Air Medal (15), Purple Heart

Date of Sacrifice: August 6, 1945 - Burbank, California, USA

Age: 24

Conflict: World War II, 1939-1945

Richard Bong, America’s “Ace of Aces” and son of a Swedish immigrant, grew up on a small farm near the village of Poplar, in northern Wisconsin. He was the oldest of nine children, born on September 24, 1920, in the nearby city of Superior—just a few miles from Lake Superior’s shoreline.

Richard became enamored with aviation as a young boy when he saw airmail planes fly over the family farm, on their way to the nearby “summer White House” retreat of U.S. President Calvin Coolidge. Bong recalled that the planes “flew right over our heads, and I knew that I wanted to be a pilot.”

After high school, Bong enrolled at Superior (WI) State Teachers College in early 1938, entering their Civilian Pilot Training program, which was launched that year for the purpose of training civilian pilots, and at the same time preparing them for the looming possibility of war.

Enlistment and Training

In late May of 1941, Richard Bong enlisted in the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet program at Luke Field, 15 miles west of Phoenix, Arizona. His gunnery instructor there was Barry Goldwater, who would later serve as a U.S. Senator and was the 1964 Republican nominee for President. Bong was described later by Goldwater as “a very bright student, [who] was already showing his talent as a pilot.”

Just one month after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II, Richard Bong earned his pilot wings on January 9, 1942, and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Army Air Force Reserves.

He worked as a gunnery instructor at Luke Field until he was transferred to Hamilton Field near San Francisco, California. There he trained to fly the Lockheed P-38 Lightening, a single-seat, twin piston-engine fighter aircraft.

Bong proved unusually skilled at aerial maneuvering and combat tactics. He also showed early signs of his fearlessness and daring. In June of 1942, Bong was cited for buzzing the house of a fellow pilot who had just gotten married. On that same day, several pilots were cited for flying a loop around the center span of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. Bong was among those accused but later denied that he was involved.

Lt. Bong’s Commanding Officer, Gen. George C. Kenney, recalls an incident where Bong flew so low along San Francisco’s Market Street that he knocked some laundry off a line and waved at people on the lower floors of some of the buildings.

Kenney remembers giving Bong a dressing down for the stunt, saying, “I don’t need to tell you again how serious this matter is. If you didn’t want to fly down Market Street, I wouldn’t want you in my Air Force. But you’re not to do it anymore, and I mean what I say.” Gen. Kenney made the young pilot help the woman with her laundry.

Deployment to the Pacific

In September of 1942, Lt. Bong was hand-picked by Gen. Kenney to be one of fifty P-38 fighter pilots sent to Australia. Bong was assigned to the 9th Fighter Squadron of the 49th Fighter Group, nicknamed “The Flying Knights.”

Lt. Richard Bong scored his first aerial victory on September 27, as he and several others engaged a larger force of enemy Japanese planes near Buna, New Guinea. He shot down two Japanese planes and was awarded the Silver Star for his actions.

A few months later, on January 7, 1943, Bong’s squadron attacked a Japanese convoy that was bringing troop reinforcements to New Guinea. He shot down two more enemy planes. On the very next day, Bong was escorting a bomber mission when he and seven fellow pilots took on an estimated 20 enemy fighters.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his action, and his citation describes Bong shooting down an enemy aircraft with a long burst from 200 yards away—a very difficult shot that brought his 5th confirmed kill, earning Lt. Bong the distinction of fighting “ace” just two weeks after his first engagement.

In March, American and Australian allied air forces attacked Japanese transport ships and destroyers carrying nearly 7,000 reinforcements to New Guinea in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. Lt. Bong shot down a Mitsubishi A6M “Zero,” highly regarded as a formidable fighting aircraft in combat. In all, 8 transports were destroyed in what was a devastating defeat for the Japanese, and a much-needed propaganda victory for the Army Air Force.

Double Ace

During WWII, only 5% of fighter pilots became aces. By April of 1943, Lt. Bong had shot down five more enemy planes, becoming a rare “double ace.” He was promoted to First Lieutenant.

On July 26 of that year, Lt. Bong spotted a formation of 20 Japanese planes over New Guinea. Outnumbered, Bong led ten P-38s in an attack on the formation, taking down two enemy aircraft himself.

When 15 more Japanese planes arrived in support, Lt. Bong ignored the greatly superior numbers of the enemy and attacked the new planes, taking down two more himself. When the engagement was over, Bong’s team of ten P-38s had shot down 11 enemy aircraft—without a single loss. Lt. Bong accounted for 4 of the 11 kills and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Close Call

Lt. Bong was promoted to Captain in August of 1943. That year, he survived a close call after drawing a Japanese fighter away from the pursuit of an injured P-38. Tricking the enemy pilot by temporarily shutting off an engine to appear distressed, Bong drew his attention and waited for the other P-38 pilot to get to the safety of a cloud bank. Turning his engine back on, Bong outraced the Japanese plane back to base.

As he prepared to land, Lt. Bong noticed his P-38 had more damage than he’d realized. Half of his tail was gone, and his ailerons were badly damaged. When he managed to touch down, he discovered that he had no brakes and that one of his wheels was punctured. He managed to stop the plane in a ditch. He was alive, but the P-38 was a total loss. On inspection, the plane had 50 bullet holes and the shield plate behind his head was pitted with dents. Both fuel tanks were punctured, but the self-sealing rubber systems inside prevented leakage.

Growing Fame, Meeting Marge

After reaching 21 confirmed kills, Captain Bong was granted leave and was able to spend the holidays at home in Wisconsin in 1943. Now a national hero, he took part in a ship launching ceremony in Superior. A group of “welderettes”—women who were pressed into service as shipyard workers—named Richard their “number one pinup boy.”

Unaccustomed to national fame and a swarming public eager for positive news, when asked to explain how he became so good at what he did Bong answered modestly, “Oh, I’m just lucky I guess. A lot of Japanese happen to get in my way. And I keep shooting plenty of lead and finally some of them get hit.”

While on leave, Bong attended a homecoming dance at Superior State Teacher’s College, where he met Marjorie Ann Vattendahl. The two began dating, and when Bong returned to the Pacific in 1944, he christened his P-38 “Marge,” and had his new girlfriend’s face painted on the nose.

Becoming the “Ace of Aces”

Captain Bong was reassigned to the Fifth Air Force Headquarters, but was allowed to freelance. On April 21 of 1944, Bong was credited with three more aerial victories, bringing his total to 28—two more than the world-famous Eddie Rickenbacker’s 26 during World War I.

Gen. Kenney promoted Bong to the rank of Major and seized the opportunity of Bong’s new record to send him home for a publicity tour. For three months Bong was on leave and traveling the U.S., urging civilians to buy bonds and generally support the war effort.

When Bong returned to duty, he was put in charge of gunnery training and ordered not to engage the enemy except in self-defense. On October 10, Maj. Bong was leading a flight, accompanying his trainees, when he shot down two more enemy planes—only in self-defense, of course.

Maj. Bong was officially a gunnery instructor and was not required to fly combat missions. But he continued to find ways to do so, and between October 10 and November 15 of 1945, he engaged in unusually hazardous sorties and shot down 8 more enemy planes.

Medal of Honor

Now the most famous and skilled pilot in American history, Richard Bong of Poplar, Wisconsin was to receive the Medal of Honor on December 12, 1944. General Douglas MacArthur gave it to him personally, in a brief ceremony at Tacloban Airfield in the Philippines, saying, “Maj. Richard Ira Bong, who has ruled the air from New Guinea to the Philippines, I now induct you into the society of the bravest of the brave: the wearers of the Congressional Medal of Honor of the United States.”

By December 17, Maj. Bong had his 40th aerial victory, and Gen. Kenney ordered him home. Bong had flown 146 combat missions and logged 400 hours of combat time. Kenney was convinced that Maj. Bong had actually achieved many more than 40 victories. There were multiple accounts of Bong giving away aerial kills to his wingmen when he had actually done the shooting.

Marriage and New Assignment

Marge and Richard were married on February 10 of 1945. Major Bong, having already given so much to his country, took on one of the most dangerous jobs outside of combat. He became a test pilot for the Army’s Air Technical Service Command. In June of 1945, Richard and Marge moved to southern California, near Muroc Lake Flight Test Base (later renamed Edwards Air Force Base). Richard was assigned as Chief of Flight Operations and Air Force Plant Representative to Lockheed Aircraft Company, which was developing and testing the new P-80 Shooting Star—the first jet fighter used operationally by the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Giving His Life for His Country

On Maj. Bong’s 12th test flight on August 6, 1945, within four minutes of takeoff, the P-80 fighter jet exploded, only some 50 feet off the ground over Burbank.

Frank Bodenhamer, a service mechanic from Lockheed witnessed the explosion, which he described to the Los Angeles Times: “We knew something was wrong when we saw a puff of black smoke come out just as he leveled off in flight. The right wing seemed to tip a little. The next thing we knew the escape hatch came off. The plane started into a glide and then sort of nosed over straight down. We saw a column of smoke go up in the air about 400 feet. It was a terrible sight.”

It was apparent to witnesses and crash investigators that Major Bong, knowing the plane was doomed, stayed with it long enough to clear the populated neighborhoods of Burbank and North Hollywood. His piloting skills came into play one last time as he managed to cause the burning wreckage to fall safely “into the only vacant lot within several blocks of bungalows.”

A witness saw Maj. Bong eject from the plane, but he was too low for his parachute to open and was caught in the explosion.

His last words to his wife Marjorie, as he left for “the office” that day were “I’ll be home around 5:30 honey, and we’ll go out to dinner and take in a show. Count Basie’s playing downtown.”

The next day, the front page of the Los Angeles Times had two stories that shocked the war-weary nation. On the same day that “Ace of Aces” Maj. Richard Ira Bong was lost, the United States had dropped the first atomic bomb on the Japanese industrial city of Hiroshima.

Legacy

When Maj. Bong died serving his country, he was just 24 years old. In his brief life, he had become one of the most decorated pilots in American history, having earned a Purple Heart, a Distinguished Service Cross, 2 Silver Stars, 7 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 15 Air Medals, and the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Maj. Richard Ira Bong is remembered and honored through the naming of a State Park—the Richard Bong State Recreation Area in southeastern Wisconsin—through the Richard I. Bong Veterans Historical Center in Superior (WI), and through the naming of numerous streets, museums, bridges, and buildings across the nation.

Numerous books have been written about Maj. Bong’s life and bravery. Among them are:

Dick Bong: Ace of Aces—written by his Commanding Officer, Gen. George C. Kenney

Dear Mom, So We Have a War—a biography written by Richard’s brother, Carl Bong

Ace of Aces: The Dick Bong Story—by Carl Bong, co-written with Mike O'Connor

Sources

Details submitted by the EAA Aviation Museum

Air Force Historical Support Division: Bong—Maj Richard Ira Bong

Recollection Wisconsin: Major Richard Bong (1920-1945)

Honor States: Richard Ira Bong

Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1945: Jet Plane Explosion Kills Maj. Bong

Our American Stories—Dick Bong, Ace of Aces: The Greatest Fighter Pilot in American History (History Guy)

Congressional Medal of Honor Society: Richard Ira Bong

Burial Site: Find a Grave